Mr. Ira Lee Taylor of Harrisburg, North Carolina, was an unassuming man. I grew up knowing him as my mailman and the father of a friend at school. It wasn’t until 2006, when I started writing a local history column for Harrisburg Horizons newspaper that I learned from another local World War II U.S. Army veteran that Mr. Taylor took part in the invasion of Normandy on D-Day.

That invasion took place 81 years ago today. Very few veterans are still here to tell their stories. Interviewing Mr. Taylor a number of times in the six years I wrote for the newspaper was one of the privileges of my life.

Instead of June 6, 1944, only being a date in a history book, it became a day of incredible heroism and sacrifice as I heard Mr. Taylor’s vivid memories of that day, the training in preparation for it, and the other battles he was in throughout the war in Europe.

Mr. Taylor served in the U.S. Army’s 4th Division. The entire 4th Division left New York City on four ships on January 19, 1944. About passing the Statue of Liberty, he said, “That was a beautiful thing. We said, ‘We don’t know whether we’ll ever see you again or not.’” Many of them never did.

More than one hundred other ships joined the 4th Division over the next three days. The Liberty Ships were carrying ammunition, food, and other supplies. He said the ships would scatter during the day, but at night they would close in almost touching each other. It took eleven days for them to cross the Atlantic and arrive in Liverpool, England.

They were transported by train from there to Devonshire, England, where they trained for the invasion of Normandy which was occupied and heavily fortified by the Germans.

He talked about how they meticulously prepared their trucks and other equipment so they would be sea worthy. They practiced loading everything up and going to the port of Plymouth. From there, they would sail down the English Channel to a place that was set up to look like “Utah Beach” in Normandy where they would train for the invasion.

Each time they set out, they didn’t know whether it was the real thing or another practice run. Of course, they did not know exactly what they were training for.

After months of planning and incredible secrecy, the invasion was scheduled for June 5, 1944. General Dwight D. Eisenhower knew he had a small window of opportunity before the moon would begin to wane.

No, June 5 is not a typo. That was set as the day for the invasion. The night before, Mr. Taylor said the troops were briefed. They were told, “The 4th Division will make the landing on D-Day. We’re sacrificing the 4th Division to make that landing. We anticipate eighty percent casualties. You’ll pass two islands in the Channel on the way – one’s Guernsey and the other one’s Jersey. You might hear some shooting and all, but don’t worry about it. That doesn’t concern you at all. Two other outfits are taking care of that.”

“The morning of June 5, the gate was locked with an MP guarding it. They wouldn’t let us out, and the boys started singing, ‘Don’t Fence Me In,’” Mr. Taylor said with a chuckle. But then the mood turned somber and they knew this was it.

Mr. Taylor’s outfit set out late on the evening of June 4. They got halfway across the English Channel and a huge storm came up. General Eisenhower was forced to call off the mission, but the invasion had to take place no later than June 6.

So Mr. Taylor’s outfit loaded up again on the night of June 5 before dark. He was on one of 499 ships that took part in the invasion.

Patton’s 3rd Division, the 90th Division, and the 4th Division were all lined up, but the 4th went out first because it was to hit the beach in the first wave.

If you’ve seen the movie, “Saving Private Ryan” or some war documentaries, you might have an inkling of an idea what the invasion was like, but I don’t think any of us can really grasp the horror of it. One thing a film doesn’t give you is the smell, but Mr. Taylor talked about the smell.

He talked about how special troops sneaked onto the Normandy coast before daybreak on June 6 and disarmed many of the mines on the beaches, right under the noses of the German soldiers. At the same time, glider troops were silently landing inland carrying tanks and infantrymen. The 82nd and 101st Airborne dropped ten miles inland, behind enemy lines.

Mr. Taylor talked about the four hundred light and heavy bombers that flew over them until six o’clock in the morning.

The 4th Division missed its target by about a mile, but started landing on Utah Beach at 6:30 a.m. on June 6, 1944.

Mr. Taylor talked about the mines and the iron crosses all over the beach as the Germans anticipated an invasion, the 50-caliber machine guns, the wounded soldiers being taken back to the Landing Ship, Tank (LST) he was on. It carried twenty tanks and 200 troops and doubled as a hospital.

Mr. Taylor was in many battles, including the Battle of the Bulge and the Battle of Huertgen Forest. He had majored in Forestry at North Carolina State University at Raleigh, so he had a particular appreciation for the Huertgen Forest of fir and pine trees, but it was there that the 4th Division lost half of its men and the forest was shattered in the fighting.

Needless to say, Mr. Taylor felt fortunate to survive the war. He came home, married his sweetheart, and got a job at the post office. Somehow, he put the horrors he had witnessed behind him, but in his later years he wanted to share his story. And I’m a better person for having interviewed him.

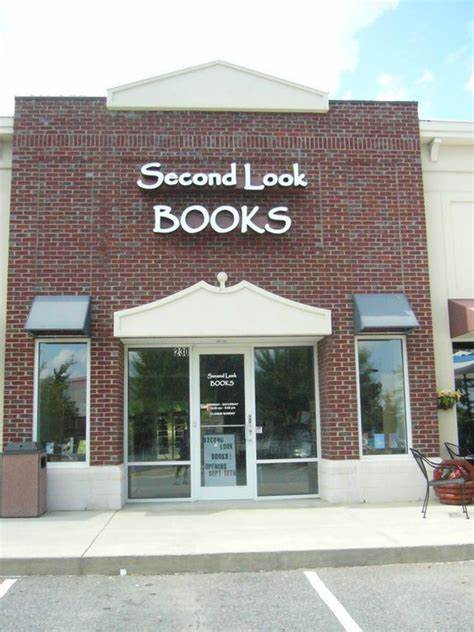

If you are interested in reading all of Mr. Taylor’s stories, my five-part newspaper series can be found in Harrisburg, Did You Know? Cabarrus History, Book 1, which is available in paperback at Second Look Books in Harrisburg and in paperback and e-book from Amazon (https://www.amazon.com/Harrisburg-Did-You-Know-Cabarrus-ebook/dp/B0BNK84LK1/). That book contains the first 91 articles I wrote for the newspaper.

Until my next blog post

Take some time today to think about the men who took part in the D-Day invasion. We owe them a debt of gratitude that we can never repay.

Janet